Submitted by Pam

Friday, January 28, 2022

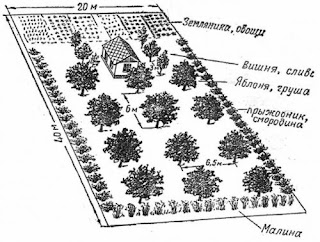

Russian Dacha Farming

Monday, January 10, 2022

The WALT Of Winter Houseplant Care

Water – According to this article, overwatering is the most common problem houseplants face in winter (although, arguably, this could be the same problem year-round). The fact is that plants need less water in winter as they enter a slow growth phase or go dormant entirely. In most cases, you should let the plant dry out thoroughly before watering. The dry air of winter will cause surface soil to dry out faster than other times of the year, so if you use your finger to check soil moisture be sure to push it in an inch or so. While the surface soil may dry quickly, it takes longer for the whole plant to dry out, so plan your watering with that in mind. One more thing: If you are using tap water and it’s very cold in winter, let it warm up before using. Frigid water is as shocking to a plant as it to us.

Air

Light

Temperature – That warm blast of air you feel when you step inside on a frosty winter day may feel wonderful to you, but chances are your plants feel differently. Houseplants just don’t like temperature fluctuations – drafts, hot air vents, a door that frequently opens to the outside, fireplaces, and radiators are all stressful to them. Plants are just not built to handle rapid temperature changes. Take a look around your house and move any plants that may be in a drafty situation. If these changes disrupt your interior design or feng shui, remember that this is only a short-term repositioning. If you have your plants positioned properly and keep your daytime temperatures between 65 °F and 75° and nighttime temperatures above 50°F, your plants should be fine.

Many of the above problems can be monitored by using one of the two Active Air meters that ARBICO Organics carries. The 2-way meter monitors moisture and pH levels, while the 3-way meter checks moisture, light and pH. Please visit our website at www.arbico-organics for more information on other products that can help your houseplants and more.Take Care

Submitted by Pam

Featured Post

Great New Products From A Long-Time ARBICO Partner.

Here at ARBICO Organics, we would not be able to provide consistently excellent products to our customers without the support of our trusted...

-

Entomopathogenic Nematodes Ever heard of a NEMATODE? You might be more familiar with their colloquial name, which is roundworm. For the p...

-

I recently had a knee injury and was ordered to stay off it for a couple of weeks. During my forced vacation, I spent most of my time on th...

-

Since I work in an insect-centric business, I decided to look at dragon insects in honor of the last episode of Game of Th...