For many people, there is some confusion regarding adelgids. It is commonly believed that they are simply wooly aphids. The fact that most people have no idea what they look like adds to this misidentification. The appearance of the invasive Hemlock Wooly Adelgid (HMA) has muddled the conversation even more. Luckily, there are explanations for all this confusion.

|

| Egg cluster of the larch adelgid |

Adelgids are small, sap-sucking

true bugs that belong to the

Adelgidae family within the insect order Hemiptera. Although they have their own family, they are closely related to aphids. At one time they were even included in the aphid family, but

taxonomists have since cleared this up. For all their similarities to aphids, they have their own unique characteristics:

• Adelgids only feed on conifers, which includes spruce, hemlock, Douglas fir, larch, pine, redwood and spruce. Although aphids may appear on conifers, adelgids will not appear elsewhere.

,%20isolated%20from%20its%20wooly%20jacket.%20The%20long,%20thread-like%20object%20is%20the%20stylet%20used%20to%20penetrate%20the%20tree%20and%20take%20up%20sap.%20A%20major%20pest%20in%20No%20America..jpg) |

| Adult balsam adelgid |

•

Adelgids only lay eggs, unlike aphids which give birth to live nymphs.

There may be other differences that scientists are still debating, but these are the two undisputed differences.

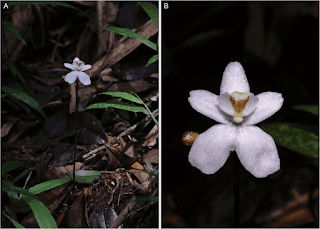

Studying and understanding adelgids has been hampered by their very nature. It is extremely hard to see and identify adelgids when they first hatch because are very small and dark and can easily hide in the conifer’s bark and foliage. As they mature, they form a fuzzy white protective coating that completely covers their bodies and can easily be

misidentified as wooly aphids or even fungi.

,.jpg) |

| Pineapple galls |

The damage done by adelgids to their hosts is usually minor and skews more to the aesthetic than the life-threatening. In other words, healthy adult trees can handle most adelgid activity (a serious infestation would be another matter). The big exception to this statement is the Hemlock Wooly Adelgid (more on that below). It’s advisable to look at adelgids as part of a healthy and diverse ecosystem as opposed to looking at them as something to control for several reasons:

|

| An opened pineapple gall |

1) The waxy coating adorning adults effectively protects them from most insecticides – particularly the less-toxic and vastly-preferable varieties.

2) Control is virtually impossible on large trees in thickly forested areas as any kind of control would require inspecting, isolating and treating the whole tree. Additionally, any sprays would need to cover all parts of the foliage and tree. These tactics would naturally require a great deal of hands-on work and the possibility of cross- and re-contamination is great. These labor-intensive types of control can only be successful on small numbers in a yard or landscape.

|

| Pine bark adelgid infestation |

3) Some adelgid species use different host plants for specific life stages. Locating and eliminating all their hiding places is challenging at best, and unlikely to be effective.

4) There are no recommended treatments for adelgids in their gall stage.

5) Any large-scale attempts at control would probably have little effect on a thriving adelgid population while causing a great deal of harm to the beneficial insects that prey on adelgids and the surrounding ecosystem they all live in.

Should you choose to tackle an adelgid infestation in your yard or garden, this article recommends a holistic approach with an emphasis on cultural controls and provides some excellent guidelines.

|

| Dying hemlocks in North Carolina |

It’s understandable if most people don’t know what adelgids are. With the rise of the Hemlock Wooly Adelgid (HWA), however, many others have become all too familiar with what an adelgid can do. This insect is an invasive species from Asia that arrived on our shore sometime in the 1950s. Since that time, it has slowly been working its way through the eastern and Appalachian forests of the United States and can now be found in 18 states and the District of Columbia.

Native hemlock species have no defenses against this insect and will slowly succumb deep in forests. HWA will stay on the same tree all their lives, feeding constantly on the nutrition that a tree needs for its branches and needles. In time, the tree’s canopy will deteriorate, the tree will begin failing and eventually die. This process can take from 4-10 years, and it is this slow and inconspicuous decline that has allowed the situation to become a crisis before most people were even aware that there is a problem. For more on just how the HWA takes down a tree, this article offers a concise explanation.

|

| Hemlock wooly adelgids |

Hemlocks are a vital part of the ancient forests of the US. They grow on millions and millions of acres and are predominant in many of them. They are an essential component to the forest ecosystem, but they are also highly valued for landscaping and in the timber business. Not to mention that the sheer beauty of these trees draws visitors to the national parks and surrounding areas they grow in. Hemlocks are bound to their communities in nearly innumerable ways and losing any of them, much less large swaths of them, is tragic on many levels.

All is not lost for the hemlocks, however. Scientists have developed management protocols for HWA. There is hope that an

adelgid-eating beetle from the Pacific Northwest can turn the tide. To get an understanding of what a successful integrated approach to an invasive species entails, read

this from the state of Maine – it includes action to take right now in the fall.

Take Care

Submitted by Pam

%20CGE0106%201%20ZS%20retouched_0.webp)

.gif)

%20infestation.jpg)

,%20isolated%20from%20its%20wooly%20jacket.%20The%20long,%20thread-like%20object%20is%20the%20stylet%20used%20to%20penetrate%20the%20tree%20and%20take%20up%20sap.%20A%20major%20pest%20in%20No%20America..jpg)

,.jpg)

.gif)